I’ve spent the last two days at the MIMSY UK User Group meeting, a gathering of people from different museums who use the collections management database MIMSY XG, to learn more about the system and how other museums use it to document their collections. It has been very interesting, and has left me thinking a bit about documentation in general…

Firstly, an admission/confesssion: when I started volunteering in a museum, back in 2007, I wanted to be a curator. A natural history curator, because that is my educational background. But also because I didn’t really know what other jobs were available in museums…I knew what a preparator was from my Palaeobiology MSc studies, but I had no idea what a conservator was, and no concept at all of what the term ‘documentation’ meant in a museum context. I think I had some woolly idea that collections were catalogued in a Victorian-style ledger, and that’s all you needed.

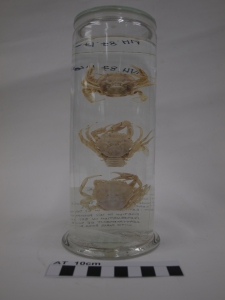

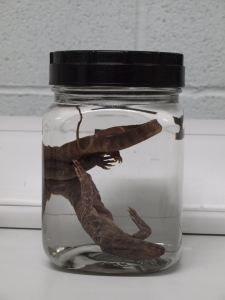

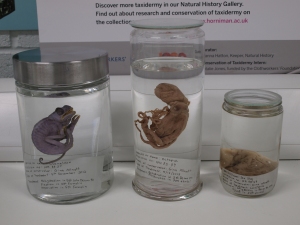

Seven years later, and documentation is almost all I do. I haven’t worked with a natural history collection in at least two years. And I do miss it, because zoology is my first love, but the more I learn about documentation, and the more I understand its importance, the more passionate I become about it! I think that’s partly because I have the right sort of pedantic mind that wants everything to be neatly organised, and partly because of my scientific background. In science, as in documentation, data is everything. The quality of your output depends on the quality of your data input. If you do not have data on your objects, then you cannot generate information about them, and you cannot interpret them for your audiences. People in our department are sometimes referred to as ‘OCD’ or ‘anal’, in a vaguely disparaging way, but I don’t think that’s fair. As museum staff, we are the custodians of our collections and the mediator between our objects and our audiences: we present objects, we build narratives around them, we use them to represent histories or ideas. And we can’t do that if we don’t know precisely what they are, where they came from, and how we acquired them. Documentation sits at the heart of everything that museums do: without information, without data, our collections are of little value.

And without this data, we would not be fulfilling our legal obligations to our collections: we need to know the history of our objects to prove their ownership, to know that they were legally collected or imported, to be accountable for our holdings, and to provide for their security. Our database technology now allows us to track everything that happens to an object, including damage and conservation work, where they go (whether that is just a change of location within the stores, or a loan to the other side of the world), and how they are used, be that as part of an exhibition, community event, or academic research project. Long gone are the days of the leather-bound ledger!